Ignatian Year Vignettes

Over the Fall 2021 Semester, we will be releasing one Vignette at a time. Please check back for new releases.

When the University of San Francisco purchased Lone Mountain College in 1978, it made one of the most important acquisitions in its institutional history. USF also continued a tradition from the Religious of the Sacred Heart, which beginning in 1932, offered an outstanding Catholic education at their San Francisco College for Women, renamed Lone Mountain College in 1970.

Vignette VIII: Acquiring Lone Mountain

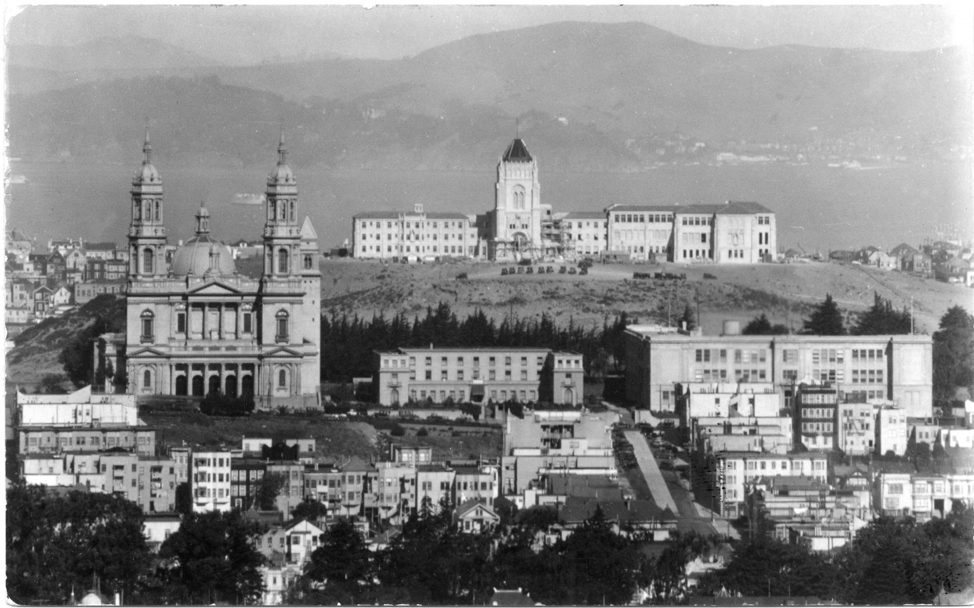

The early Spanish explorers and settlers in the area called the 488-foot rise of land El Divisidero, or “lookout point.” It is an apt description for what is now the Lone Mountain Campus of the University of San Francisco. The campus offers a 360-degree view of the surrounding world: downtown San Francisco and the East Bay communities; a substantial portion of San Francisco Bay; the Golden Gate and the Marin Headlands; the Pacific Ocean, including the Farallon Islands on a cloudless day; and some of the southern portion of the city, punctuated by Mount Sutro. The first archbishop of San Francisco, Joseph Alemany, purchased Lone Mountain in 1860, and it soon became Calvary Cemetery. During the late nineteenth century, the spectacular views from Lone Mountain were shared by gravediggers, mourners, and other visitors to the 23-acre cemetery. Successful gold miners, silver barons, wealthy businessmen, and politicians were all laid to rest on Lone Mountain until 1900, when the city outlawed any more internments at the location. Following the earthquake of April 18, 1906, many San Franciscans journeyed to Lone Mountain to stand amid the gravestones and watch two-thirds of their city burn to the ground. The Masonic Cemetery, just south of Lone Mountain, housed the remains of an additional 19,000 deceased San Francisco residents, often from more modest backgrounds than those buried on Lone Mountain.

During the first three decades, the Religious of the Sacred Heart made numerous changes to their college. In 1941, 105 curving stone steps, modeled after the Spanish Steps in Rome, were built to lead up to the building from Turk Street. Today at the top of the steps is a marble statue by Yoko Kubrick, who grew up in Japantown, a few blocks from Lone Mountain. The sculpture, entitled “Tides,” was commissioned by the San Francisco College for Women, Class of 1968, to celebrate their 50th anniversary. The class raised $100,000 for the sculpture and the surrounding Sacred Heart Garden. In 1948, the Underhill building was added on a plateau east of the main building and below the tennis courts. It housed science and nursing classrooms and laboratories, an art studio, a music room, and other facilities. On December 26, 1935, after heavy rainfall, 30,000 tons of dirt slid down the west side of Lone Mountain, burying Parker Avenue. The slide destroyed a road circling around to the back of Lone Mountain. After years of litigation, Parker Avenue was reopened in 1951.

The San Francisco College for Women was resilient in the face of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the stresses of World War II. The current Heritage Room on Lone Mountain is dedicated to the legacy of the San Francisco College for Women and the Lone Mountain College. By 1960, nearly 800 women were enrolled at the college, many supported by the generosity of alumnae of the institution. In 1963, a new structure was added to the North side of Lone Mountain. It included a two-story Spanish Gothic style chapel, cafeteria and faculty dining rooms, a separate six-story building providing housing for 200 students, a 550-seat theater, a ballroom, and other units. In 1968, the Rossi Wing (named for Esther Rossi, an active Sacred Heart alumna who died in 1963) was added to the east side of the building.

By the mid-1960s, the popularity of women’s colleges in the United States had begun to decline, and enrollment at the San Francisco College for Women was especially hard-hit when USF became completely coeducational in 1964. In 1970, in the face of a severe enrollment decline and a consequent fiscal crisis, the college became coeducational, changed its name to Lone Mountain College, and introduced an experimental curriculum in place of the traditional liberal arts focus. Enrollment continued its downward spiral; however, alumnae support withered, and the institution faced insurmountable financial problems. In 1977, Sister Gertrude Patch, the last in a line of six presidents of the college drawn from the Religious of the Sacred Heart, resigned.

In 1977, the new Lone Mountain College president, Berndt Kolker, approached the new president of USF, John Lo Schiavo, S.J., about a secured loan of $700,000 to help the college through the spring semester of 1978. The loan agreement included an option to purchase the entire 23-acre campus, including its buildings and equipment, after the spring semester ended. On June 15, 1978, following a series of discussions among the leaders of USF and a financial analysis regarding the current and projected USF need for additional classroom space, offices, and student housing, Fr. Lo Schiavo, with the unanimous backing of the USF Board of Trustees, announced that USF would purchase Lone Mountain for $5.8 million. Fr. Lo Schiavo described the purchase as “the most significant expansion decision in our 123-year history.” Although USF had recently faced its own financial problems, Fr. Lo Schiavo’s administration had taken major steps in addressing those financial problems; enrollment at USF was increasing; and alumni, friends, and foundations had by the time of the acquisition pledged $1.6 million toward the purchase price. The transition from Lone Mountain College to the University of San Francisco was eased by the hiring of key employees from the Lone Mountain College, preserving the student records of alumni, and accepting students to USF from their Lone Mountain College programs.

Fr. Lo Schiavo wrote to the USF community: “I see a renewed enthusiasm and optimism which will fulfill a dream of many of our pioneer benefactors, Jesuit fathers, and long-term faculty who have believed that USF all along was destined to become one of the pre-eminent educational institutions in the West. The Lone Mountain acquisition, while a substantial challenge, will bring us close to touching that realization.”

The Lone Mountain campus of the University of San Francisco currently houses classrooms; residence hall rooms for undergraduate and graduate students; and a multitude of administrative offices, including those of the president, provost, other administrators in academic affairs, university development, marketing and communications, information technology services, and business and finance, among others. In 1999, Loyola House was built on the northeast corner of Lone Mountain for the USF Jesuit Community, which currently houses 30 Jesuits. In 2002, the university completed work on Loyola Village, a 136-unit residential complex for students, faculty, and staff, located at the northeast base of Lone Mountain. Most of the current residents of Loyola Village are students. In August of 2021, three hundred of USF’s second-year students moved into USF’s newest residence hall, Lone Mountain East. It will eventually house 600 students. In this sublime complex, Spanish-style architecture blends with the architecture of original building from 1932. The new residence hall is comprised of two buildings, one with four floors, and one with five floors, connected by an aerial walkway. It has four interior courtyards, and adjacent to the residence hall is a new dining facility, offering some of the most spectacular views in San Francisco.

From 1932 to 1978, the Religious of the Sacred Heart offered an outstanding college education in the finest Catholic tradition on Lone Mountain. That tradition continues today on the Lone Mountain Campus of the University of San Francisco.

Sources:

Information on the history of Lone Mountain can be found in A College on the Hill: San Francisco College for Women/Lone Mountain College, 1930-1978, by Joanna Gallegos; in Legacy and Promise, by Alan Ziajka, pages 321–323; in San Francisco: Magic City, by Fremont Older, pages 37–38; in the Spring 1990 issue of USF Alumnus, page 1; in an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, February 12, 1984; in the Foghorn, October 9, 1991; and in USFnews Online, in its February 4, 2003, June 1, 2004, and August 8, 2004 issues (www.usfca.edu/usfnews). The quote from Fr. Lo Schiavo on USF’s purchase of Lone Mountain appears in the USF Alumnus, July 1978, page 2.

Alan Ziajka, Ph.D.

University Historian Emeritus

ziajka@usfca.edu

March 15, 2022

The University of San Francisco became fully coeducational in 1964, after many thwarted attempts to achieve that status. Today, 65 percent of the overall student population is female, and many of the school’s alumnae are leaders in government, law, business, education, nursing, and the health professions.

Vignette VII: Becoming Coeducational

They were intrepid pioneers embarking on a challenging educational journey: the first women to enter St. Ignatius College, the heretofore all-male Jesuit institution of higher education in San Francisco. The year was 1927, and the women included Margaret McAuliffe, Anne Sullivan, and Ruth Halpin, the first women in the evening division in the new College of Commerce and Finance (now the School of Management); and Anne Shumway, Bertha Ast, and Helen Byrne, the first female students in the School of Law. The undergraduate day division of the school would not become coeducational until 1964, but in 1927, these first female students set the stage for what followed. By 1930, when the school was renamed the University of San Francisco, there were 20 women studying law (out of a total law school enrollment of 265), and there were eight women among the 110 students in the evening division of the university. By the fall of 1944, World War II had reduced the total student enrollment to a meager 196 full-time day students and 135 evening division students, of whom seven were women law students and 58 were women in the evening division. Approximately 20 percent of the tuition revenue that was generated in 1944, came from female students. With the end of World War II, enrollment of males, buttressed by the G.I. Bill of Rights, dramatically increased at USF.

In 1948, a department of nursing was established in the College of Arts and Sciences, and by 1954, the program had become the independent School of Nursing, further adding to the number of female students at USF. In the same year, the dean of faculties at USF, Raymond Feeley, S.J., began to advocate for the inclusion of women in all the programs at the university. In 1951, Fr. Feeley became academic vice president, and he, along with many other administrators and faculty members at USF, pushed for the inclusion of women in the undergraduate day division of the university, in the face of opposition from several quarters, including the Catholic hierarchy in Rome. Despite petitions by USF faculty and administrators for the admission of female undergraduate students to the day division of USF, petitions supported by a large segment of USF alumni and even nuns in local Catholic high schools, the Catholic hierarchy in Rome continued to oppose full coeducational status for USF as the fall semester of 1963 got underway.

John Connolly, S.J., the president of USF from 1954 to 1963, repeatedly raised the issue of the inclusion of women in the day division of the school with John Mitty, the Archbishop of San Francisco. For years, the archbishop failed to support that inclusion. In 1961, however, Archbishop Mitty finally gave his approval to USF to become a fully coeducational institution. Authorities in Rome, however, still balked at the idea. When Fr. Connolly became provincial of the California Province in 1963, he persisted with the Jesuit authorities in Rome, with the full backing of his successor, the new president of USF, Charles Dullea, S.J. Finally, in October 1963, the announcement was made that USF had received permission from Rome to accept women in all divisions of the university, and in the fall of 1964, USF became fully coeducational. Among the 475 women undergraduates who registered for classes on September 15, 1964, 235 were enrolled in the School of Nursing, 232 were in the College of Arts and Sciences, and 8 women enrolled in the School of Business Administration. Frances Ann Dolan, formerly assistant dean of women at the Jesuit-run Marquette University in Milwaukee, was selected in August 1964 to be USF’s first dean of women. She was on hand to greet the first fall class of women in the regular day division in the history of the institution. The number of female applicants made it possible for the admissions office to be very selective, so that the first women students were academically strong. USF President Charles Dullea, S.J., described how well the women fit into the academic life of USF, and indeed raised the caliber of the student body academically. Years later, Fr. Dullea remarked, “The fellas called the women the DAR—Dammed Average Raisers.”

In 1966, Hayes-Healy Hall was built, providing the first residence hall for approximately 350 women students on campus. The hall was the result of a donation from Ramona Hayes-Healy and John Healy, as a memorial to their parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Hayes and Mr. and Mrs. Richard Healy. In the first years of coeducation at the undergraduate level at USF, women students faced strict curfews and dress codes, as did men, though less severe. In 1968, for example, the general regulations for the university included the following: “Women students are expected to be appropriately dressed when on campus. Mini-mini skirts and pant dresses are not acceptable campus wear. Women students may not wear sports clothes (slacks, jeans, stretch-pants, capris, Bermudas) in or around any campus building, including the lounge areas of the women’s residences, or when attending basketball games. Sports clothes are appropriate when participating in active sports and when going to or returning from the area of active sports. ‘Short’ shorts, jeans, and cut-offs are not acceptable at any time.” For men, the rules simply stated that “blue work Levi trousers and Bermuda shorts should not be worn in class, in the library, or in the dining room of the University Center.” In 1969, the last vestiges of dress codes were eliminated from the university’s regulations.

In the fall semester of 1978, women comprised 50 percent of the student population at USF, which in that year stood at 6,931. By the fall semester of 2021, there were 10,034 students at USF, and 65 percent were women. Many of the school’s alumnae are leaders in government, law, business, education, nursing, and the health professions. Prominent female graduates of USF include London Breed, current San Francisco Mayor; Rear Admiral Kerry Page Nesseler, Assistant Surgeon General of the United States; Sheila Burke, former Chief Operations Officer and Undersecretary for the Smithsonian Institute; Martha Kanter, former Undersecretary of the U.S. Department of Education; Patricia Barron, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy; Barbara Jones, former Presiding Justice of the California Court of Appeal; Heather Fong, former San Francisco Police Chief; Barbara Garcia, former Director of Public Health for San Francisco; Sheryl Davis and Susan Christian, San Francisco Human Rights Commissioners; Valerie Ziegler, California Teacher of the Year for 2010; Cynthia Rapaido, California Assistant Principal of the Year for 2013; Ginnifer Hutchison, winner of the Writers Guild Award for Television; Sabeen Ali, CEO of Angel Hack and founder of Code for a Cause; Vicky Nguyen, Emmy-award winning investigative and consumer reporter for NBC news; and Nora Wu, the first Asian woman to hold a leadership role in the history of Pricewaterhouse Coopers International as Vice Chairwoman and Global Human Capital Leader.

From the first women pioneers in 1927 to today, the dramatic increase in the percentage of women at USF, and at colleges and universities across the nation, is attributable to several factors. These include historical and social changes in the role of women in our nation, such as the expanding role for women in the labor force during World War II; the women’s liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s; federal and state legislation prohibiting discrimination against women; and the consequent opportunities for women in professions for which higher education is critical, such as business, law, medicine, and other professions that had once been largely the exclusive domain of men. Most important of all, however, has been the powerful role of individual women, such as the first women at St. Ignatius College in 1927, as agents in producing attitudinal, political, educational, and social change in the United States.

Sources

The road to full coeducational status for women at USF is recounted in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849 –1969 by John McGloin, S.J., pages 204–210; and in Legacy and Promise, by Alan Ziajka, pages 291–295. Information about the first women students at St. Ignatius College can be found in the Ignatian, 1928, pages 53 and 55; the Ignatian, 1929, page 78; and The University of San Francisco School of Law: A History, 1912–1987 by Eric Abrahamson, pages 39–42. Reflections by Anne Dolan, Fr. Dullea, and some of the first women in the classes that began in 1964 and 1965 appear in the USF Alumnus, Winter 1990, pages 1 and 7. Dress code regulations in the 1960s are listed in the student handbook, The Hilltopper, 68–69, page 33. Prominent female graduates of USF are noted in The University of San Francisco Fact Book and Almanac, 2005–2019, by Alan Ziajka. Statistics on the current enrollment at USF were furnished by Joseph Henson, Associate Vice Provost of Institutional Research and Analytics, University of San Francisco.

Alan Ziajka, Ph.D.

University Historian Emeritus

ziajka@usfca.edu

February 15, 2022

World War II produced dramatic changes at the University of San Francisco: enrollment declined by 76 percent as most students volunteered or were drafted into the armed forces, the financial stability of the institution was seriously jeopardized, and 106 of the school’s young men died in combat. Thanks to a visionary president, a successful fundraising drive, and the G.I. Bill of Rights, USF survived and flourished after the war ended.

Vignette VI: World War II and the Last Full Measure

The University of San Francisco underwent profound changes during World War II. Enrollment dropped precipitously as the young men of the university volunteered for the armed forces or were drafted. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, enrollment in all divisions of the institution stood at 1,337. By the beginning of the spring semester of 1945, total enrollment had declined to 321 students. The onset of the war also produced a change in the USF academic calendar. Beginning in the fall semester of 1942, the traditional two-semester schedule for undergraduate students was replaced with a tri-semester system in which the traditional six-week summer session was lengthened to a regular semester. This change was made to accelerate students’ completion of their programs due to their expected service commitments, and to give students the opportunity to go to officer’s candidate school when they reported for active duty.

Given the dramatic enrollment decline and the consequent budget shortfall during the war, USF President William Dunne, S.J., traveled to Washington to enhance the ROTC program and obtain other military training programs for the university. Fr. Dunne’s efforts began to bear fruit in July 1943, when the United States government established an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) at USF. This program, for the training of engineers and other technical personnel, brought 300 students from all over the country to the university, adding to the institution’s geographic diversity. Many former ROTC students were also reassigned to USF for further training. On the north side of the campus, along Golden Gate Avenue, eight temporary buildings, including barracks, offices, and an infirmary, were hastily built. These buildings survived well past the end of the war for classroom use, and only with the construction of the Harney Science Center in 1965 and University Center in 1966 were the barracks finally removed from campus. The accelerated ASTP program, with its heavy demand for intensive science courses, initially helped stabilize USF’s uncertain financial situation. In March 1944, however, the government announced the discontinuation of the ASTP program nationwide due to the desperate need for overseas personnel. At USF, the program was officially closed in 1944, and the students were ordered to active military service. The termination of this program, the ending of student deferments, and the conscription of vast numbers of college-age youths further added to the economic problems of the university. By 1944, revenue had declined enormously, and USF was running a monthly deficit of more than $6,000.

Due to USF’s mounting financial problems, a committee of alumni and friends was formed by Fr. Dunne to raise money for the struggling institution. The committee was headed by Florence McAuliffe, graduate of the St. Ignatius College class of 1905 and former president of the San Francisco Bar Association; William McCarthy, former San Francisco postmaster, fire commissioner, and county supervisor; and Daniel Murphy, an executive with Crocker Bank. This was the same trio, working with Matthew Sullivan, dean of the USF School of Law, which had helped to secure the purchase of the Masonic Cemetery in 1934, which would underpin the eventual post-war expansion of the university. In 1936, McAuliffe had also helped to secure funding for the construction of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. The wartime fundraising campaign by McAuliffe, McCarthy, and Murphy brought in $150,000 for USF, a modest sum even by 1940s standards, but a sufficient amount to help ease the university through a challenging economic period.

While USF was struggling to survive economically, thousands of its former students were serving overseas in all branches of the service, and more than 50 former science and pre-medical students were in the army, navy, or marine medical corps risking their lives to save others. Throughout World War II, an alumni publication called the Don Patrol kept the University of San Francisco community informed about the many young men of the school who were in active military service abroad. The publication reported on the promotions and decorations received by former USF students, provided information about those killed or missing in action, and often quoted from servicemen’s letters from the front. The August 1943 issue, for example, noted that up to that point in the war, 1,900 former USF students had joined the military, 15 had been killed, and five were missing in action or had been captured by the enemy. The same issue reported that Colonel Jim Sullivan of the Army Medical Corps, class of 1912, had been taken prisoner during the fall of Bataan in the Philippines. Colonel Sullivan did not survive the war. The August 1943 issue also described “soldier-doctor, Bill Reilly, class of 1923” as a “good-Samaritan for American and Axis troops alike somewhere in North Africa,” and the February 1945 issue reported that Captain Paul Tanaka, class of 1933, was with the Army Medical Corps “somewhere” in France.

To help servicemen return to civilian life, Congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the G.I. Bill of Rights. Once it was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt, it became arguably one of the most important pieces of legislation in the history of the nation. It entitled former military personnel to guaranteed loans for buying homes and setting up businesses, provided unemployment insurance, and most importantly for the nation’s colleges and universities, allocated funds to cover educational expenses. Thousands of individuals who had previously been deterred from attending college because of cost now had a major portion of their education subsidized by the federal government. This single law had a monumental educational and social effect on the nation and on its institutions of higher education, including the University of San Francisco, which saw its enrollment soar after the war ended.

A combined USF and St. Ignatius High School service flag (the two schools were joined until 1959) was displayed above the altar of St. Ignatius Church during the war. The flag included white stars representing faculty, students, and alumni who served, and gold stars representing those who lost their lives. By the end of the war, the flag had more than 3,000 white stars and 136 gold stars, of which 106 represented USF students, alumni, and faculty members who gave their lives during World War II. Continuing the tradition from World War I, the service flag was blessed at special ceremonies held in St. Ignatius Church on Sunday, May 24, 1942, and on George Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1944. At both ceremonies, William Dunne, S.J., president of USF, delivered sermons. The 1944 ceremony was announced as a “religious patriotic service of remembrance,” beginning with an academic and military procession. James Lyons, S.J., chaplain of a military unit then undergoing training at USF, sang Mass, and the enlarged service flag was rededicated to those, who in Abraham Lincoln’s immortal phrase from another war, gave “the last full measure.”

Sources

World War II is described in most standard texts on United States history, including The United States: An Experiment in Democracy, by Avery Craven and Walter Johnson, pages 803-843. The impact of the war on USF is covered in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849–1969 by John McGloin, S.J., pages 170–174. The most complete history of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) during World War II is found in Scholars in Foxholes: The Story of the Army Specialized Training Program in World War II by Louis Keebler. The wartime editions of the Adios, the USF Senior Class Yearbook from 1941 to 1944, also contain significant information about USF’s involvement in the war. The USF catalogs from 1942 to 1945 detail the academic requirements for science, liberal arts, business, and law students, and the accelerated time frame for graduation resulting from wartime demands. Enrollment statistics for USF during World War II were furnished by the USF Center for Institutional Planning and Effectiveness. Information and direct quotes drawn from the letters written by World War II servicemen appear in several issues of the Saint Ignatius Church Bulletin, dated November 16, 1943; November 20, 1943; August 21, 1944; March 18, 1945; and April 26, 1945. Copies of the Don Patrol and the 1940 USF catalog are found in USF’s archives in the Gleeson Library.

Alan Ziajka, Ph.D.

University Historian Emeritus

ziajka@usfca.edu

January 12, 2022

The Great Depression of the 1930s posed major financial challenges for the University of San Francisco. Nevertheless, when the opportunity arose to purchase a significant parcel of land adjacent to the school, the Jesuits acted, setting the stage for transforming the university.

The stock market crash of October 1929 ushered in a worldwide depression that had major effects on the nation, the city of San Francisco, and the university that would soon adopt the city’s name. Like the city itself, the Jesuits’ experiment in education faced major economic challenges during the 1930s—finances were a constant source of concern, and enrollment was flat during most of the decade. The institution began the decade, however, on several optimistic notes, including a celebration of its 75th anniversary in 1930, a new name (the University of San Francisco replaced St. Ignatius College), and a U.S. Supreme Court decision paving the way for a major land acquisition that underpinned expansion of the university after World War II. The co-curricular programs that had flourished during the 1920s, including athletics, drama, and debate, survived the economic woes of the 1930s, though desperately needed improvements for the library, science equipment, and classroom facilities were financially impossible. Graduates of the university found the job market terrible, and alumni contributions were minimal.

The absence of funds for needed academic improvements weighed heavily on Harold Ring, USF’s president from 1934 to 1938. In a 1936 letter to the alumni, he wrote, “Our students and faculty must carry on their work under the difficulties of restricted library, laboratory, and classroom space. The rich endowments of many of our sister private and public institutions have encouraged us to think that we too shall someday emerge from our present difficulties and be able to offer our students adequate library, laboratory, and gymnasium facilities. The present endowment of USF consists solely of the endowment of man; that is, the religious teachers who give their services without other compensation than their sustenance and the lay teachers who carry on so efficiently in the face of so many sacrifices.” As the nation and the university finally began to emerge from the Great Depression in 1939, there was a glimmer of hope that the fortunes of USF might improve. Soon, however, the world would be plunged into a world war that would further test the institution.

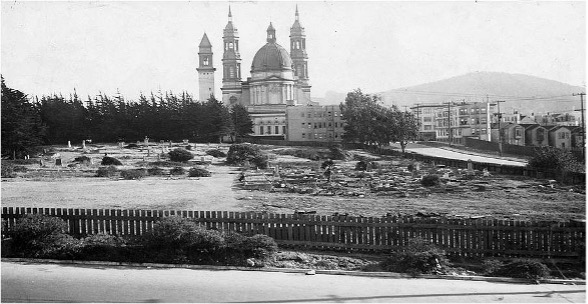

After years of litigation and negotiations, approximately 14 acres of the Masonic Cemetery, situated just north of the Liberal Arts Building and Saint Ignatius Church, were purchased by USF in 1934. This photo was taken on October 14, 1930, during USF’s Diamond Jubilee celebration. Courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

In 1930, during the first full year of the Great Depression, the United States Supreme Court made a decision that was to have a major impact on the development of the University of San Francisco. After years of litigation, the Supreme Court ruled that an old Masonic cemetery, covering approximately 28 acres of land located directly north of the new Liberal Arts Building on Fulton Street, could be sold to any prospective bidder. Looking toward the eventual expansion of their institution, the Jesuits had sought for years to buy this cemetery, which extended from Parker Avenue to Masonic Avenue and from Turk Street to Fulton Street, not including the property already owned by the Jesuits where St. Ignatius Church, the faculty residence, and the Liberal Arts Building stood. Although burials had not been permitted on this property since 1901, there was strong opposition on the part of 17 cemetery lot owners to the removal of the estimated 19,000 bodies interred within the cemetery limits.

When the removal issue was brought before the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1928, an ordinance authorizing the removal of the bodies passed with the support of the Masonic Cemetery Association, owner of the property. This association was eager to sell the property and argued that the land had become a “menace to health, a wilderness frequented by vagabonds and a barrier to fire apparatus.” The cemetery lot owners fought the ordinance in the federal circuit court, which issued an injunction against it. This injunction was appealed all the way to the United States Supreme Court, the appeal being handled by Matthew Sullivan, graduate of St. Ignatius College, former Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court, and dean of the school’s College of Law. On March 10, 1930, the Supreme Court dissolved the injunction and upheld the ordinance, thus clearing the way for the Jesuits to buy the cemetery.

After several years of negotiations, the Masonic Cemetery Association agreed to sell the entire cemetery to the Jesuits for $690,000. With the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929, however, and with the Jesuits’ growing financial burdens, USF was able to purchase only approximately half of the cemetery property, consisting of 14 acres of land south of Golden Gate Avenue, at a cost of $290,000, with an option to purchase the rest of the land by 1934. Unfortunately, the Jesuits could not raise the funds necessary to exercise this option, and the land between Golden Gate Avenue and Turk Street was sold to private developers. The deeds to the property south of Golden Gate Avenue finally passed to the Jesuits in March 1934.

In the last months of the negotiations between the Masons and the Jesuits, unclaimed headstones and tomb monuments at the Masonic Cemetery were removed and used for seawalls, landfill, and roads along the San Francisco Bay, and most of the bodies interred in the cemetery were hastily exhumed by the Masons and transported to the Woodlawn Cemetery in Colma. The removal crews missed many of the bodies, however, because the deceased had often been buried in inexpensive nineteenth-century wooden coffins that eventually deteriorated, and the canvas bags that had sometimes been used to wrap the deceased disintegrated over time, the bones mixing freely with the sandy soil. Additionally, bodies sometimes shifted from their original locations under marked tombstones in the wake of earthquakes and other land movements, and many other coffins and mausoleums had been buried under tons of dirt removed from the excavation site of the San Francisco College for Women on Lone Mountain and remained unnoticed by the removal crews. In later decades, therefore, when foundations were constructed for new buildings on campus, overlooked bones were frequently unearthed. When contractors were excavating the foundation for Gleeson Library in 1950, one of their large earthmovers crashed through the roof of a buried mausoleum, and coffins containing bodies were churned up by the tractor operator. In 1966, when ground was broken for the foundation of Hayes-Healy Residence Hall and the adjacent garage, the work crew came upon so many bones and skulls that they refused to continue working until the human remains were removed from the site.

In July 2011, when workers started to excavate the site for the new John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation, they found human remains. Work was immediately halted, and the San Francisco Medical Examiner’s Office was contacted. A team of professional archaeologists was also called in to ensure that all human remains and coffins were excavated with care and that cultural material was preserved. The archaeologists eventually uncovered 55 coffins, 29 human skeletons, some additional skeletal remains, mortuary artifacts, grave markers, funeral hardware, and ornaments. At this location, where nineteenth-century San Francisco citizens were once buried, twenty-first-century USF students, some destined to save lives as future physicians, now study science and conduct research.

Sources

The stock market crash of 1929 and the Depression of the 1930s are described in most standard texts on U.S. history, including The United States: An Experiment in Democracy by Avery Craven and Walter Johnson, pages 704708. A good summary of the 1930s in San Francisco appears in The San Francisco Almanac by Gladys Hansen, pages 49–53, and in Fire and Gold: The San Francisco Story by Charles Fracchia. The 1930s at the University of San Francisco are described in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849–1969 by John McGloin, S.J., pages 152–170; in Legacy and Promise by Alan Ziajka, pages 194–215; and in the limited number of issues of the Ignatian published during that decade (1930–1932, 1937). Information about the excavation of the site for the John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation, is found in the unpublished Final Archaeological Resources Report for the University of San Francisco Center for Science and Innovation Project, City and County of San Francisco, California by Archeo-Tec, Inc. (Allen G. Pastron, principal investigator).

Alan Ziajka, Ph.D.

University Historian Emeritus

ziajka@usfca.edu

December 8, 2021

World War I and the associated global influenza pandemic had a profound impact on the University of San Francisco. The enrollment decline caused by the war, along with a host of financial problems, drove the institution to the brink of bankruptcy.

The illuminated crosses on the steeples of St. Ignatius Church showed brightly through the thin fog that enveloped the surrounding neighborhood on the evening of May 12, 1918. It was the date of a special church ceremony to bless a service flag for those students and alumni of the University of St. Ignatius, as the University of San Francisco was then known, who were then fighting and dying in World War I. The nearly four-year-old church, on the corner of Fulton Street and Parker Avenue, had celebrated its first Mass on August 2, 1914, two days before the major powers of Europe began hostilities. St. Ignatius Church served during World War I, as it had in the past and would in the future, as the focal point for the extended university community to come together to pray, to offer blessings to those members of the community who were not present, and to assist people in finding meaning in those events that transformed their lives.

Beginning in the summer of 1917, 380 students and young alumni from the University of St. Ignatius joined millions of other Americans at war in Europe. The university’s young men, mostly first- and second-generation Europeans, would find themselves fighting alongside or against other young men, also of European ancestry. The university itself would experience a significant drop in enrollment due to the military draft and the call for volunteers. After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, and the Selective Service bill was passed by Congress in May of that year, the number of students at the university who were 18 years of age or older declined to less than 100. During World War I, the University of St. Ignatius established a federally sponsored army-training program on campus, a precedent for the army-training program during World War II and a harbinger for today’s ROTC program. In student debates and publications, the institution would for the first time consider issues of war and peace on an international scale, and tragically, ten young men from the University of St. Ignatius would not return from the “War to End All Wars.”

Four of the three hundred-eighty University of St. Ignatius students who served in World War I: (clockwise, from the top left) Wallace Sheehan, Fred Butler, Mark Devine, and Joseph Sullivan. Their photos appeared in the June 1918 issue of the Ignatian, the school’s literary magazine. Courtesy of University of San Francisco Archives.

By early June 1917, more than 9 million American men had registered with local officials whom the War Department authorized to supervise the draft. Before the war ended, almost 3 million men had been inducted into the army. An additional 2 million Americans volunteered for the various armed services. In August 1918, the president of the University of St. Ignatius, Patrick Foote, S.J., announced that the United States Commissioner of Education had requested that as many young men as possible stay in college to receive government-supervised military training and qualify as officers. On September 6, 1918, students were informed that the University of St. Ignatius had been accepted as a unit in the national Students Army Training Corps. Within a few days, the poignant sound of taps, played by a sole bugler of the University of St. Ignatius Army Training Corps, floated across the campus at 10 o’clock every evening. The notes he played resonated throughout the halls of the labyrinth building on the corner of Hayes and Shrader Streets that comprised the university, then known as the “shirt factory.” The building was so named because of its resemblance to many actual shirt factories built in San Francisco after the Earthquake and Fire of 1906. The sounds of taps also symbolized major changes at the University of St. Ignatius, catalyzed by World War I.

The University of St. Ignatius College of Engineering, which started in 1912 with 29 students, was dramatically affected by World War I, as was the entire university. Despite a promising beginning, the College of Engineering was a victim of World War I, and it closed its doors in 1918 when enrollment at the University of St. Ignatius, and in its College of Engineering, dropped precipitously as many students and faculty left for the war, some never to return. With the university’s overall decline in student enrollment, and with the closing of its College of Engineering, the school’s leadership could no longer justify using the term university in its title, and in 1918 it resumed its old name, St. Ignatius College. It would be another 12 years before the term university was restored. In 1930, at the urging of various alumni groups, St. Ignatius College was renamed the University of San Francisco.

On November 11, 1918, an armistice ending World War I was signed by Germany and the Allies. The human losses from the war were almost beyond comprehension: nearly 10 million soldiers died in combat, another 3 million men were missing and presumed dead, and millions of European civilians died from military actions, disease, and starvation. A pernicious strain of influenza began among the soldiers stationed in the United States and Europe at the close of the war. It rapidly spread to the civilian population and became a global pandemic. By 1920, the influenza pandemic had taken an estimated 50 to 100 million lives around the world, more than of 5 percent of the world’s population. In the United States alone, 675,000 perished, including approximately 3,500 citizens of San Francisco. Among the dead of World War I, were 112,432 American servicemen, half of whom died of the influenza that swept through military camps in Europe and America. Among the ten former University of St. Ignatius students who died during the war, three succumbed to the influenza.

The deadly strain of influenza first appeared in San Francisco during the last week of September 1918. By October 9, the City of San Francisco had at least 169 cases of influenza. A week later, that number had increased to 2,179. As the number of cases began to increase, the city’s Board of Health issued a series of recommendations to the public on how best to avoid contracting influenza. People were advised to stay off streetcars during peak rush hours, asked to avoid crowds, and told to pay attention to their personal hygiene. Streetcar conductors were ordered to keep the windows of their cars open in all but rainy weather, dance halls were closed, hospitals were ordered to accept only those patients who absolutely required their care, and hospital physicians and nurses were instructed to wear masks when treating flu patients. On October 17, Mayor James Rolph met with members of the Board of Health, the Red Cross, the United States Army and Navy, the United States Public Health Service, and theater, movie house, and other amusement place owners to discuss the growing pandemic. After some discussion, the Board of Health voted to close all places of public amusement, ban all lodge meetings, close all public and private schools, and prohibit all dances and other social gatherings. The director of public health, William Hassler, quarantined all naval installations. The board did not close churches, but instead recommended that services and socials be either discontinued during the pandemic or held in the open. City police were directed to ensure compliance with the order. The Liberty Loan drive to raise money for the nation’s efforts during the war, however, was allowed to continue. San Francisco officials also mandated face masks for all of those who had contact with the public, including physicians, nurses, barbers, hotel and rooming house employees, bank tellers, druggists, store clerks, and others serving the public. On October 21, the Board of Health met and issued a strong recommendation to all residents to wear a mask while in public. Mayor Rolph, the Board of Health, the Red Cross, and the Chamber of Commerce ran a full-page newspaper ad, declaring: “Wear a mask and save your life.” By October 26, the Red Cross had distributed 100,000 masks.

Despite the city’s efforts, the pandemic continued to spread, although the number of new cases began to decline. By the end of October 1918, San Francisco had a total of nearly 20,000 cases of influenza and over 1,000 deaths. By the first week of November, however, the situation had improved enough that the Board of Health voted to lift the various bans, starting on November 16. Hotels and restaurants could resume their musical entertainment, but no dancing was allowed. Schools were permitted to reopen on November 25, and people flocked to the city’s theaters, movie houses, and sports arenas the first day they reopened. The downtown theaters all held charity performances, with proceeds going to the United War Work campaign. At noon on November 21, San Franciscans removed their masks as a whistle sounded across the city, the result of Mayor Rolph revoking the mandatory mask ordinance.

Confidence that the epidemic was almost over in San Francisco was premature. On December 7, Mayor Rolph was informed by the Department of Health of a “slight recrudescence of the disease.” Mayor Rolph publicly declared that the influenza had returned to San Francisco and requested that residents once again wear masks. Business closures and bans on public gatherings were not reinstituted, as it was believed that re-masking would be all that was necessary to rid the city of the disease permanently. When the number of new cases reported to health authorities dipped slightly, it provided hope that a second peak was not on its way. This hope was short lived. On January 10, 1919, with over 600 new influenza cases reported that day, the Board of Supervisors voted to re-enact the mask ordinance. Sentiment was so strong, however, against the mask ordinance that several influential San Franciscans, including a few physicians as well as a member of the Board of Supervisors, formed “The Anti-Mask League,” which held a public meeting to denounce the ordinance and to discuss ways to put an end to it. Over 2,000 people attended the event. On February 1, 1919, the league got their wish. Mayor Rolph proclaimed the mask ordinance rescinded after the Board of Health determined that the pandemic situation had improved enough that masks was no longer necessary. Most of the citizens of San Francisco removed their masks, and families, organizations, and institutions slowly resumed life, as it existed before the pandemic. In the face of inconsistent city efforts, San Francisco had nearly 45,000 cases of influenza and approximately 3,500 deaths during the fall of 1918 and the winter of 1919. In mid-February 1919, the United States Public Health Service released figures on the nation’s pandemic, and San Francisco was reported as having suffered the most deaths per capita of any major American city.

Because the University of St. Ignatius was largely a military training camp in September 1918, it did not close under the city’s mandate, though the university did suffer under the strains of the influenza pandemic. Many teachers and students became ill, and one high school teacher, Austin Howard, S.J., died. Fr. Austin was also head of the Red Cross in the High School. At that time, St. Ignatius High School was linked with the University of St. Ignatius, and both divisions shared the same building. Many sick students and teachers from both divisions were sent for treatment to St. Mary’s Hospital, one block north of the school, to be treated by physicians and nurses from the Sisters of Mercy. Richard Gleeson, S.J., former president of Santa Clara College, former provincial of the California Jesuits, and the new prefect of St. Ignatius Church, arrived in San Francisco just as the 1918 influenza pandemic was raging through the city; the Jesuit community; and the faculty, staff, and student populations of the University of St. Ignatius. Fr. Gleeson, for whom the main USF library was named in 1950, helped tend to the many individuals associated with the church and college who were struck down by the pandemic, and he helped minister to the sick in the nearby Japanese community, including assisting Jesuit Brother Matsui to run the Japanese mission in the community. Other individuals, such as Pius Moore, S.J., who served as president of the university from 1919 to 1925, were “brought to death’s door,” as he also ministered to the hard-hit Japanese community in San Francisco, located two miles from the school. Many of the families and friends of those connected to the school also became ill, and two recent graduates of the school, from the classes of 1916 and 1918, died from influenza in early 1919.

With the armistice of November 1918, the Students Army Training Corps at the University of St. Ignatius began to disband, and by the end of 1918, it was completely demobilized. Because of the sharp decline in student enrollment following America’s entrance into World War I, the university faced mounting financial problems. Other factors also contributed to the institution’s financial duress. The destruction of St. Ignatius Church and College in the 1906 earthquake and fire forced the Jesuits into major indebtedness. By the end of 1906, the purchase of land on the corner of Hayes and Shrader streets, and the building of a temporary church and college on that site put the Jesuits $230,000 in debt. In 1909, the debt rose another $100,000 from a loan secured by the Jesuits to purchase a site on the corner of Fulton Street and Parker Avenue for their new church. Although the original estimated cost for the church was $300,000, by the time the church was dedicated on August 2, 1914, the overall institutional debt stood at more than $835,000, most of which was from cost overruns on construction of the church. By January 1919, the debt had risen beyond $1 million (equivalent to about $13 million today), and a financial crisis was at hand. Each year, $50,000 in interest was due various banks and loan companies. For months, no interest was paid on the principal, and the Jesuits of San Francisco were facing bankruptcy.

In January 1919, Francis Dillon, S.J., provincial of the California Province, decided to assist the Jesuits of San Francisco during their economic crisis. He met with Edward Hanna, the archbishop of San Francisco; Patrick Foote, S.J., the president of the University of St. Ignatius and rector of the Jesuit community; and several prominent businesspersons and civic leaders. The result of these meetings was a public acknowledgment of the financial crisis; the formation of the St. Ignatius Conservation League, headed by Dennis Kavanagh, S.J.; and a public appeal for aid. Members of the St. Ignatius Alumni Society and many other organizations promised to solicit funds. The Jesuits of St. Ignatius Church and College were also asked to make personal appeals for funds. On April 15, 1919, Archbishop Hanna issued a proclamation calling for the citizens of San Francisco to come to the aid of St. Ignatius Church and College.

The call for financial support for St. Ignatius Church and College was made loud and clear. An answer to that call came soon as many prominent San Franciscans came to the aid of the institution during its time of economic need. In August 1919, during the first phase of the fund-raising efforts, the Jesuits decided to sell their vacated property on the corner of Van Ness Avenue and Hayes Street, where St. Ignatius Church and College had stood before its destruction in the 1906 Earthquake and Fire. San Francisco realtors purchased the property for $311,014. A second phase of fund-raising was coordinated in 1920 by Richard Gleeson, S.J., prefect of St. Ignatius Church, who succeeded Dennis Kavanagh, S.J., as director of the St. Ignatius Conservation League. On January 31, 1921, money was raised at an event sponsored by the Conservation League, held at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium, billed as “America’s Biggest Whist Tournament,” and featuring card-playing, bands, and dancing. Over the next three years, additional benefit plays, concerts, and dinners were held by the Conservation League. On May 24, 1924, a festival was held, and items such as automobiles, hope chests, washing machines, and a Spanish bungalow were raffled off, enabling St. Ignatius Church and College to nearly finish repaying its long-standing debts.

From 1919 to 1925, during the presidency of Pius Moore, S.J., the huge financial debt that had brought St. Ignatius Church and College to the brink of financial disaster was reduced from more than $1 million to $150,000. The various fund-raising activities during that period, plus the sale of the Van Ness location, saved the institution. Within two years, the Jesuits of San Francisco were financially prepared to embark on another venture: the construction of a new college on Fulton Street, the nucleus of the current home of the University of San Francisco.

Sources

The impact of World War I on the University of St. Ignatius is described in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849–1969 by John McGloin, S.J., pages 103 and 104; in Legacy and Promise by Alan Ziajka, pages 127 through 145; and in all the issues of the Ignatian, the school’s literary magazine, published between 1914 and 1919. One of the best books on the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 is John Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. San Francisco’s response to the influenza outbreak of that period is recounted in The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, San Francisco (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Center for the History for the History of Medicine, 2016, https:www.influenzaarchive.org/index,html.)

Alan Ziajka

University Historian Emeritus

University of San Francisco

ziajka@usfca.edu

November 11, 2021 (Armistice Day/Veterans Day)

The San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906 destroyed the University of San Francisco, then known as St. Ignatius College, and the adjacent St. Ignatius Church. The disaster forced the Jesuits and their lay colleagues to muster their faith, courage, and resolve to rebuild their institution.

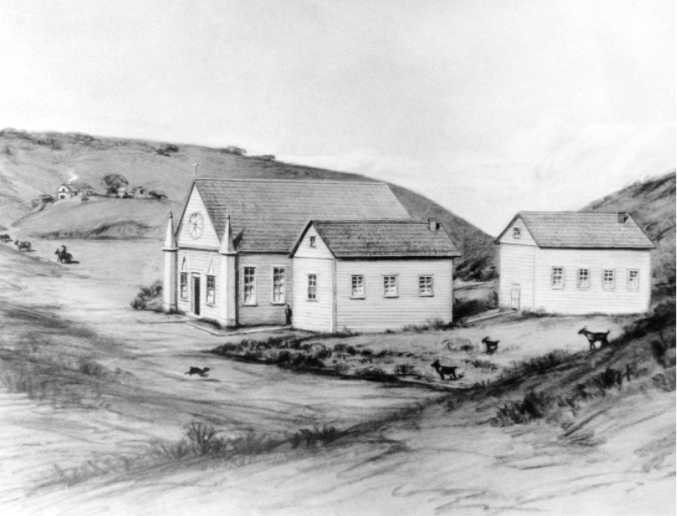

On the evening of October 19, 1905, Jeremiah Sullivan—graduate of St. Ignatius College, first president of the college’s alumni association, and San Francisco Superior Court Judge—was the toastmaster for a celebratory banquet marking the 50th anniversary of the founding of the institution. The banquet served as the grand finale to a five-day Golden Jubilee honoring the day, October 15, 1855, when St. Ignatius Academy, the antecedent of the University of San Francisco, first opened its doors to three young men who crossed the sand dunes surrounding an undeveloped Market Street, entered a small wooden building, and became the first students at the Jesuit educational experiment in the City by the Bay.

On the night of the 1905 banquet, Judge Sullivan, and the other dinner speakers, reflected on the growth of the institution from its beginnings as a one-room schoolhouse, adjacent to a small Jesuit church and residence, to a magnificent building on Van Ness Avenue that occupied a full city block replete with world-class scientific laboratories, some of the finest libraries in the Western United States, and the best-equipped gymnasium in the city. The school was also connected to a majestic church capable of holding 4,000 people. By 1905, scores of the school’s alumni had become leaders in the civic, legal, banking, business, and religious communities of San Francisco, and many of the 800 young men attending the school that fall were destined for prominent careers in those same fields. None of the banquet celebrants could have predicted, however, that in six months the great school and church they had helped build would be completely destroyed by the most devastating earthquake and fire ever to strike an urban area on the North American continent, forcing the leaders of St. Ignatius College to muster their faith, courage, and resolve to ensure the continuity of their institution.

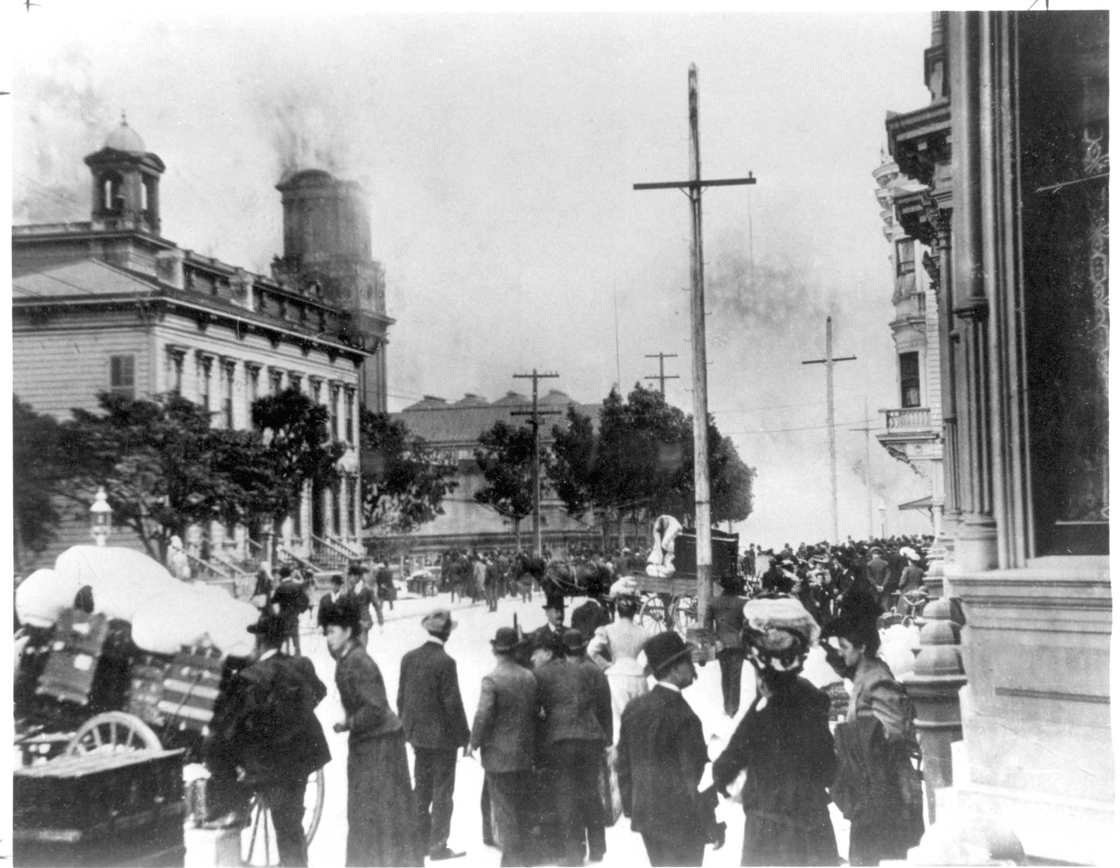

The initial temblor of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake was recorded at 5:12 on the morning of April 18, 1906, and lasted for 40 seconds. There was a pause for 10 seconds, and then a second even more violent shaking lasted for an additional 25 seconds. Several more temblors shook the entire Bay Area throughout the day. Although the Richter scale was not developed until 1935, seismologists estimate that the 1906 earthquake was approximately 7.9 on the 10-point scale—the equivalent of 15 million tons of exploding TNT. It was one of the strongest earthquakes ever to strike North America, and it was recorded by seismologists as far away as Birmingham, England. In San Francisco, the damage from the earthquake was widespread. Huge splits opened up in many of the city’s streets, chimneys and towers collapsed, and frame buildings toppled or leaned severely to one side after the initial temblors. Most of the newly completed city hall collapsed, the victim of the earthquake and of several years of graft-inspired inferior materials and workmanship. Neighborhoods in the city built on landfill that had once been part of the bay, such as in the South of Market area, suffered the greatest damage, and many buildings there were destroyed.

Although most San Franciscans were still asleep in their beds when the first shaking started, the 44 Jesuits of St. Ignatius Church and College, on the corner of Van Ness Avenue and Hayes Street, were already up when the earthquake struck. No sooner had the Jesuits and many other San Franciscans begun to respond to the damage and injuries of the initial earthquake than from the rubble-strewn streets of the city, menacing columns of smoke began to rise. The fires resulted from fractured gas lines, crossed and broken electrical wires, overturned stoves, cracked chimneys, and flammable chemicals from spilled and shattered bottles. To make matters worse, when firefighters hooked up their hoses to fight the fires, they found that in almost every case, there was no water pressure. The earthquake had broken the main water lines from the city’s two largest reservoirs and had caused more than three hundred fractures to the subsidiary water lines within the city. Raging fires throughout San Francisco, in the wake of the earthquake, eventually became one giant conflagration that took on a life of its own, fed by thousands of wooden buildings standing adjacent to each other throughout the city. In that uncontrollable inferno, temperatures reached 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to melt marble, iron, and steel, crumble sandstone, and dissolve glass into liquid. Smoke from the fire rose five miles into the atmosphere, and the flames could be seen from 50 miles away. In the ensuing fire, all of St. Ignatius College, including its state-of-the-art scientific equipment and laboratories, museums, libraries, the gymnasium, and the magnificent St. Ignatius Church, were destroyed in less than an hour. None of the Jesuits of St. Ignatius Church or College, nor their students, were killed, though several were injured. The horrific San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 killed more than 3,000 people, left 225,000 people homeless out of a total city population of 400,000, leveled 514 city blocks spread over four square miles in the heart of the city, and destroyed more than 28,000 buildings. The estimated value of the loss was $500 million, four-fifths of the 1906 property value of San Francisco, or approximately the size of the federal budget in 1906.

St. Ignatius Church starting to burn following earthquake of April 18, 1906. Courtesy of University of University of San Francisco Archives.

Due to the destructive fire that rapidly spread through St. Ignatius Church and College, most of the Jesuits lost all their personal belongings and had only the clothes they were wearing at the time of the earthquake. The President of St. Ignatius College, John Frieden, S.J., and 11 other priests initially took shelter in the Convent of the Sisters of the Holy Family, at the invitation of the nuns and at the suggestion of Archbishop Patrick Riordan. The Jesuits occupied the second floor of the building, and the first floor was set aside as an emergency hospital. The convent, on the corner of Hayes and Fillmore streets, was seven blocks west of Van Ness and was spared by the fire. Many of the other Jesuits of St. Ignatius Church and College, after aiding injured and dying citizens, made their way to Santa Clara and stayed at a house offered by friends across the street from Santa Clara College. St. Ignatius College students of the graduating class of spring 1906 were permitted to complete their work at Santa Clara College.

President Frieden and some of the Jesuit community stayed at the Holy Family Convent in San Francisco until May 22, 1906, when they moved to the home of Mrs. Bertha Welch on Eddy Street. Mrs. Welch, a wealthy benefactor who had had made major donations to the Jesuits of San Francisco in prior years, offered the Jesuit community the complete use of her mansion. She had been in New York at the time of the earthquake, and when she heard of the loss of St. Ignatius Church and College, she telegraphed her offer to the Jesuits. Fr. Frieden secured Archbishop Riordan’s approval for this relocation and for the establishment of a small temporary chapel in Mrs. Welch’s home to continue the Jesuits’ ministry. Soon, 18 Jesuits from the dispersed community moved into the house. From the home of Mrs. Welch, and with her continuing financial assistance, the Jesuits of San Francisco turned to the questions of where, when, and how to rebuild their church and school.

Shortly after the earthquake and fire, the Sisters of Mercy, an order of nuns with whom the Jesuits had a long history in San Francisco, offered the Jesuits a parcel of land at the end of Hayes Street to occupy rent-free for two years. After two years, the Sisters of Mercy planned to start construction on a new Saint Mary’s Hospital at that location. The Jesuits politely declined this offer, however, because they believed they would need a temporary site for more than two years. Instead of this location, Fr. Frieden first leased, and then purchased for $67,500, two lots owned by Mr. and Mrs. M. H. deYoung, on the corner of Hayes and Shrader streets. By early June 1906, plans were developed for the erection of temporary buildings at this location. Like much of San Francisco, St. Ignatius Church and College was going to rise rapidly from the ashes.

On Sunday, July 1, 1906, less than three months after the San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed St. Ignatius Church and College, ground was broken for a new location for the institution. The site, on the corner of Hayes and Shrader streets, just two steep blocks south of today’s campus, was to be only a temporary home. In fact, however, the building erected at this location served the Jesuits, their lay colleagues, and students for more than two decades. The rambling wooden building that comprised St. Ignatius Church and College came to be known as “the shirt factory” because of its resemblance to several hastily built structures south of Market Street, some of which actually housed shirt factories.

St. Ignatius College reopened its doors in the shirt factory on September 1, 1906, to 271 students ranging from sixth grade through college. In 1926, with a significant increase in student enrollment, work was begun on a new Liberal Arts building, now named Kalmanovitz Hall. In 1927, this new building was dedicated, and St. Ignatius College moved to its present location on Fulton Street. St. Ignatius Church moved from the corner of Hayes and Shrader streets to its current location in 1914, and the high school division moved from the shirt factory in 1929 to a building on the corner of Turk Street and Stanyan Boulevard, the current site of USF’s Koret Health and Recreation Center. The old shirt factory was eventually torn down, and the site is now the location of the Sister Mary Philippa Health Center, one of the buildings of St. Mary’s Medical Center. In 1930, St. Ignatius College was renamed the University of San Francisco.

Today on the USF campus, a giant winged bird is engraved on the front wall of University Center. It is the phoenix, a mythological bird that is consumed by fire but rises renewed from the ashes. The phoenix, which looks across a plaza at the John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation, symbolizes the rebirth of the City of San Francisco and the University of San Francisco after the earthquake and fire of 1906. Like the phoenix, the University of San Francisco was destined to rise from the ashes.

Sources

The earthquake and fire of 1906 is described in Denial of Disaster: The Untold Story and Photographs of the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906 by Gladys Hansen and Emmet Condon; in Fire and Gold: The San Francisco Story by Charles Fracchia, pages 99–127; in Historic San Francisco: A Concise History and Guide by Rand Richards, pages 171–189; in San Francisco: Magic City by Cora Older, pages 1–8; and in Legacy and Promise by Alan Ziajka, pages 73–85. The impact of the 1906 earthquake and fire on St. Ignatius Church and College is detailed in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849–1969 by John McGloin, S.J., pages 72–80, and in numerous primary documents, including the personal reminiscences of John Frieden, S.J., president of Saint Ignatius College in 1906, that are housed in the USF archives.

Alan Ziajka

University Historian Emeritus

University of San Francisco

ziajka@usfca.edu

October 15, 2021 (USF Founder’s Day)

Science and faith have always been compatible at the University of San Francisco. As early as the 1870s, St. Ignatius College, the forerunner of USF, had one of the best science programs in the nation. In 1876, the Mechanics Institute of San Francisco, the leading professional science association of the era in San Francisco, reported, “We may well congratulate ourselves for possessing within our midst in this young city and state, such facilities for scientific education as St. Ignatius College affords to our rising generation, and such a cabinet of philosophical apparatus, second to none in the United States.” Among the college’s stellar faculty members were Joseph Neri, S.J., professor of natural philosophy. In addition to teaching chemistry and physics at the college and publishing in scholarly journals, Fr. Neri frequently gave public lectures to the citizens of San Francisco on science topics. In 1874, Fr. Neri demonstrated the first electric light in San Francisco, using a “mammoth magneto-electric machine” from Paris. On July 4, 1876, to commemorate the centennial of the nation’s independence and the founding of San Francisco, Fr. Neri attached the device to arc lights mounted on top of St. Ignatius Church and on a wire running to a building across the street. When an Independence Day parade came by in the evening, Fr. Neri flipped a switch and illuminated all of Market Street. The electric light he generated could be seen from 200 miles away.

Fr. Neri’s use of electricity to illuminate San Francisco secured national recognition for the college and was a decade before Edison’s invention of the incandescent lamp. Fr. Neri’s electrical demonstrations so impressed the civic leaders of San Francisco that they installed “an electrical system of illumination then regarded as the largest in the world.” In September 1879, the newly organized California Electric Light Company (the antecedent of the Pacific Gas & Electric Company), operating out of a power station next door to St. Ignatius College, supplied the first commercial electricity to San Francisco’s initial three-dozen electric lamps. In the same year, San Francisco’s premier hotel, the Palace Hotel, and its most fashionable playhouse, the California Theater, installed brilliant arc lights modeled on those pioneered by Joseph Neri, S.J., the Jesuit priest who brought electricity to San Francisco.

.png)

Market Street in San Francisco was first illuminated by Joseph Neri, S.J. during the national and city celebration of July 4, 1876. This 1900 photo depicts Market Street at night, looking down to the Ferry Building. Courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Fr. Neri was in the tradition of many great Jesuit scientists, mathematicians, and teachers who made enormous contributions to science, scholarship, and public service. These individuals included Christopher Clavius, S.J. (1538–1612), considered one of the most influential mathematicians of the Renaissance, who was the inventor of the Gregorian Calendar still used today and a superb astronomer who greatly influenced Galileo. His papers were described in the earliest editions of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, and his commentary on Euclidean geometry became the standard textbook on the topic in the 17th century. Fr. Clavius joined the Jesuits the year before Ignatius of Loyola died. Matteo Ricci, S.J. (1552–1610), brought Western mathematical and astronomical concepts and scientific instruments to China, became the first court mathematician in Peking, translated Fr. Clavius’ works into Chinese, and published the first comprehensive maps of China available in Europe.

In 1669, Ferdinand Verbiest, S.J. (1623-1688) was invited by the Chinese Emperor to direct the imperial court’s official observatory in Peking. Fr. Verbiest began his new job in the imperial court during the Qing Dynasty by installing the latest astronomical instruments in the Chinese observatory. One of those instruments was an equatorial armillary sphere, an astronomical device for measuring time, creating, and correcting calendars, and tracking celestial bodies, such as the Moon and Mars. The armillary sphere, built by Fr. Verbiest in 1673, was six feet in diameter, and its fine-tuned astronomical instrumentation, which included moving rings and a dragon and lion, represented the integration of Western and Chinese science, art, and religion in the late 17th century. An exact replica of this armillary sphere stands in front of the John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation on the USF campus. The armillary sphere symbolizes much of what the Jesuits have promoted for more than 480 years: scientific rigor, academic excellence, cultural respect and accommodation, and the compatibility of science and faith.

Other prominent Jesuit scientists include Jose de Acosta, S.J. (1540–1600), a pioneer in geophysical sciences and meteorology, who provided the first detailed description of the geography and culture of Latin America, made scientific observations of volcanoes and earthquakes, and analyzed altitude sickness in the Andes Mountains. Nicolas Zucchi, S.J. (1586–1670), made ground-breaking contributions to the use of the reflecting telescope and served as a papal legate to the court of Emperor Ferdinand II, where he developed a long-term scientific correspondence with Johannes Kepler, the originator of the heliocentric theory of the solar system. Roger Joseph Boscovich, S.J. (1711–1787), was a physicist, astronomer, and philosopher who developed the first coherent description of atomic theory. His work, Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis, argued that the ultimate elements of matter were atoms, which contained centers of force. His book appeared more than a century before the birth of modern atomic theory. Honoré Fabri, S.J. (1607–1688), developed post-calculus geometry, and wrote more than 30 treatises on a wide range of subjects: the heliocentric theory of the solar system, Saturn’s rings, tidal phenomena based on the actions of the moon, magnetism, and optics. Much of his work was described in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Francesco Lana-Terzi, S.J. (1607–1688), is considered by many to be the father of aeronautics. His descriptions of potential flight were based on mathematical calculations and principles of physics, and were translated into several languages, discussed by European scientists for a century, and underpinned the development of the first successful flight of a hot-air balloon in 1783. In honor of the legacy of these and other Jesuits, 35 lunar craters are named after Jesuit scientists.

The Jesuit scientific tradition is alive and well today at the University of San Francisco. The John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation, completed in 2013, contains 11 teaching labs and 6 classrooms (ranging from a 16-seat wet lab for chemicals and other biological matter to a 47-seat lecture room), houses state-of-the-art scientific equipment for use by undergraduate and graduate students, and can accommodate as many as 500 students at one time. Through creative use of space, the building facilitates the integration of all the sciences, including biology, chemistry, physics and astronomy, environmental science, computer science, engineering, mathematics, biochemistry, analytics, and kinesiology. The classrooms, teaching labs, storage areas for scientific equipment, and open spaces are adjacent to each other to encourage the exchange of ideas across disciplines, creative problem solving, and student-centered teaching and learning. The grounds surrounding the Lo Schiavo Science Center feature drought-resistant and all-native California plants, and an elaborate drainage system leading to a 28,000-gallon underground cistern for recycling water to the building’s gardens. The building’s temperature is regulated by a computer that opens and closes windows as the temperature changes. Channel glass is used throughout the building to maximize light and keep the building warm. The building is certified by the U.S. Building Council as a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) gold building because of its energy efficiency, recycled and renewable non-toxic building materials, solar power collection, and water efficiency landscaping.

USF students at work in a lab in the John Lo Schiavo, S.J. Center for Science and Innovation. University of San Francisco

In the fall of 2020, USF launched an innovative science program in engineering. Its antecedent was a civil engineering program at St. Ignatius College from 1912 to 1918. That earlier program was a victim of World War I, and it was discontinued due to the enrollment and fiscal losses at the college during that war. Like the current engineering program, however, its mission was to educate the whole person in the Ignatian tradition. In the current program, the three engineering concentrations are environmental engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and sustainable civil engineering. Today’s engineering program at USF embraces an innovative, inclusive, and applied education focusing on design, creation, and resourcefulness. It provides students the technical, leadership, and business skills they need to succeed as professionals, and the self-confidence, empathy, and cultural competence necessary to be responsible engineers to effect meaningful change. The program is committed to social justice, and encompasses community-engaged scholarship, teaching, research, and interdisciplinary programming relevant to real-world problems locally, regionally, and internationally. The program includes a new physical space on campus, an innovation hive, in which to imagine and build real-world solutions. The innovation hive is the physical and conceptual center of engineering at USF, featuring multiple learning-center spaces that are accessible to the entire USF community.

The University of San Francisco’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic reflects the institution’s commitment to science. The institution followed all the national scientific guidelines and strictly adhered to city and state rules and recommendations based on science. When the pandemic first struck in early 2020, USF rapidly shifted to online classes, largely shut down the campus by March 2020, and established strict protocols for reopening the campus in the fall of 2021, including requiring vaccinations among all returning students, faculty, staff, and visitors; mandating face covering; and calling for contact tracing and testing among those exposed to the virus. Faculty members and students in the School of Nursing and Health Professions administered vaccinations to hundreds of the most vulnerable members of the surrounding community at the Koret Health and Recreation Center on campus. Nursing students and faculty also assisted at other community vaccination sites in the Bay Area, Orange County, and Sacramento.

In the 1870s, Joseph Neri, S.J., brought electric light to the people of San Francisco and changed the city forever. One hundred and fifty years later, USF faculty members and their students are changing the world and making it a better place. This tradition of using science for the common good stretches back to the first years of the Jesuit Order in the 16th century, and flourishes at today’s University of San Francisco.

Sources

Fr. Joseph Neri’s life and work is portrayed in The First Half Century: St. Ignatius Church and College, by Joseph Riordan, S.J., (pages 157, 188-193, 200-204, and 326); in Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849-1969 by John McGloin. S.J., (pages 30-31); by Mel Gorman, in the Journal of Chemical Education, Vol. 41, November 1964, (page 628); and in the USF archives, file RG1, Box 27. Taryn Edwards, at the Mechanics’ Institute of San Francisco, provided the Report of the Eleventh Industrial Exhibition of the Mechanics’ Institute of San Francisco in 1876. The work of representative Jesuit scientists is covered in Lighting the City, Changing the World: A History of the Sciences at the University of San Francisco by Alan Ziajka (pages 5-6).

Alan Ziajka

University Historian Emeritus

University of San Francisco

ziajka@usfca.edu

September 8, 2021