USF Academic Integrity Committee Annual Report 2019-2020

Jonathan Hunt, Chair

July 15, 2020

Introduction

The Academic Integrity Committee presents this year-end report in the interests of equity, fairness, and transparency. We hope the information in this report will help members of the USF community participate more effectively in supporting a culture of integrity at our institution.

There is good news in this report. We see a low incidence of academic integrity violations generally. In particular, there is a low incidence of second offenses, indicating that the USF Honor Code works by alerting students to the importance of integrity in academic work and giving them opportunities to learn, grow, and correct for lapses or errors in judgment.

We suspect, however, that incidents are under-reported (factors influencing faculty to under-report are treated in the Discussion section). Reporting is an essential component of USF’s process, emphasizing to students and the community that USF faculty will not look the other way, and helping ensure that students get the educational opportunities they deserve before leaving the USF community.

In view of the data in this report, the AIC makes the following recommendations:

- We see serious disparities in patterns of reporting and sanction, suggesting that USF’s academic integrity system, despite the good will of faculty and staff, may magnify inequalities in educational opportunity.

- We must ensure that USF students have opportunities to foster their integrity and strengthen their ability to navigate a morally complex world. USF must do a better job of enacting cura personalis through the academic integrity system.

- Faculty members deserve evidence-based professional development in supporting integrity and in responding to violations

Academic Integrity Incident Reports 2019-2020

Overview

For information about the USF Honor Code and the Academic Integrity Committee, see https://myusf.usfca.edu/academic-integrity. This site, last revised in 2014, includes the complete text of the Honor Code, explanations of policies and procedures, and resources for students and faculty. This is also the portal for reporting suspected violations of the Honor Code.

In 2019-2020, the Academic Integrity Committee received 66 incident reports regarding violations of the Honor Code.. These reports involved 67 students who received some kind of sanction or penalty from faculty members. This is roughly consistent with 2018-19, which saw 59 incident reports involving 65 individuals.

Fewer than 5% of students reported had a previous report on record (3 out of 67).

Matching global trends, there is a perceived rise in “contract cheating” (where a student employs another person to do their academic work). In 15 incidents, faculty suspected contract cheating (most commonly, ghostwriting of essays or exams). For more on this trend and responses to it, please see “Contract Cheating” in the Discussion section.

In approximately 90% of overall cases, the role of the AIC is centered on documentation and record-keeping. USF’s faculty members are empowered to determine appropriate responses to dishonesty in their own courses, as consistent with the Honor Code, department or program policies, and their own course policies. As per the Honor Code, the AIC investigates cases and levies additional sanctions only under specific circumstances:

- if the report indicates a second offense or a grave offense

- if the student contests an accusation and requests an investigation

In 2019-20, the AIC conducted 8 investigations. Of these, 4 were due to students reported for a second offense; 3 were due to serious or grave offenses; 1 was initiated by a student. This is nearly double the number of investigations compared with the previous year, although the increase does not necessarily represent a trend, as the yearly number of investigations is highly variable.

Following a finding of a violation of the Honor Code, the AIC votes to impose a sanction. The four options are: no sanction; letter of censure; suspension; or dismissal/revocation of degree. In the case of a vote for suspension or dismissal, the AIC vote is presented to the Provost as a recommendation.

In 2019-2020, the AIC voted to impose 4 sanctions (in addition to course-level sanctions imposed by faculty members):

- 3 students received Letters of Censure

- 1 student was recommended for dismissal from the University.1

For comparison, in 2018-2019 issued 3 letters of censure and 1 recommendation for dismissal.

Note that the AIC never rules on matters of grading. Any grade appeal by students must be conducted according to procedures outlined in the USF-USFFA Collective Bargaining Agreement and in University policy.

Please see Appendix 2 for a more detailed summary of the Honor Code and AIC procedures; the full Honor Code is found here: https://myusf.usfca.edu/academic-integrity/honor-code.

1 One 2019-2020 investigation is pending as of this writing.

Who is reported?

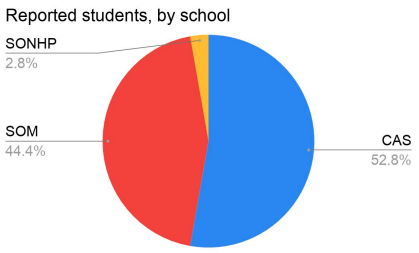

54% of students reported are in the College of Arts and Sciences, 44% in the School of Management, and 3% in the School of Nursing and Health Professions. No School of Education students were reported for Honor Code violations in 2019-2020. The School of Law has a separate disciplinary procedure.

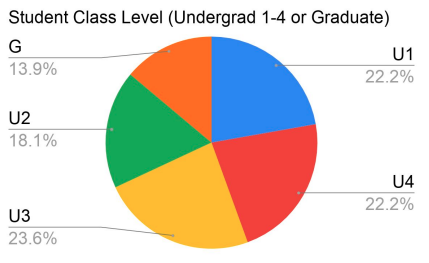

Students are distributed evenly across all class levels. The slight variations indicated in the chart at right are not considered significant, given the total number of students reported.

Transfer students accounted for 10 out of 57 undergraduate students reported, or 17.5%.

Graduate students, who make up about a third of the USF student population, accounted for only 15% of students reported.

48 international students were reported. This group included students from every global region, with Asia (including East and South Asia) accounting for 75% of the international students reported.

Of the US students reported for violations, 12, or two-thirds, appear to be members of under-represented groups in higher education.

Who reports?

Reports were received from faculty teaching in more than 20 different departments and programs. One report was received from a student; one was anonymously submitted.

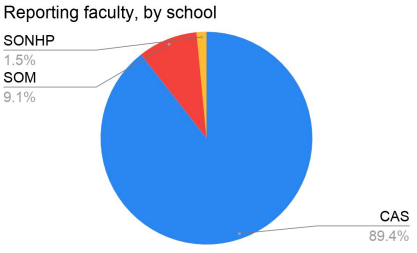

More than 90% of reports received were filed by faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences;. reports from faculty in the School of Management accounted for 8%. A small number of reports were received by non-faculty members (staff, students, and anonymous). Of reporting faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences, 48% were in Arts & Humanities, 7% in the Social Sciences, and 38% in the Sciences.

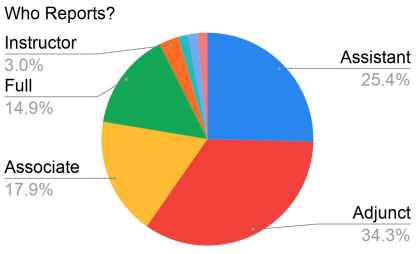

Of faculty reports, 34% were submitted by adjunct faculty, followed by full-time assistant professors (25%), associate professors (18%), full professors (15%) and Instructors (3%). The AIC does not have data on whether full-time faculty are appointed as tenure-line or term.

What offenses are reported?

The incident report form used by the AIC requires indication of the type of violation of the Honor Code (see below). Respondents must choose from 8 checkboxes and may select multiple boxes:

- Abuse of Library Privileges

- Abuse of Shared Electronic Media

- Cheating

- False Citations

- Falsifying Academic Documentation

- Plagiarism

- Submitting False Data

- Submitting the Same Work for Multiple Assignments

Plagiarism is the most commonly reported offense (48 incidents). Plagiarism is a large category that includes everything from poorly documented sources to copy-and-paste patchwriting to fully ghostwritten material. Faculty frequently note Turnitin reports as an alert to copy-and-paste plagiarism; in 15 incidents, however, faculty suspected that student work was not copied but wholly composed by another person.

Cheating made up the bulk of the remaining reports (17 incidents). The most common form of cheating was unauthorized accessing of information during an exam (including on-site and take-home exams) using computer, phone, or notes. Unauthorized collaboration with other students was also reported.

What are the consequences?

USF’s Honor Code empowers faculty to decide on course-level consequences for violations of the Honor Code. Faculty members report that they often refer to department-level policies (sometimes included in required syllabus statements), and frequently consult with department chairs or other colleagues in determining consequences for violations.

The most common consequence imposed by faculty was a grade penalty on the assignment. In 48 cases (approximately 75% of the total), students received either a zero or a failing grade on an assignment where cheating or plagiarism occurred. In 8 cases, the penalty was a reduced grade on the assignment. In the case of major assignments, such as final exams, an assignment-level penalty sometimes caused the student to fail the class; however, most students received assignment-level penalties for homework or quizzes and were able to pass the class. A small number of faculty members report offering students pathways to mitigating the penalty, such as re-doing an assignment.

In 8 instances, the consequence of cheating or fraud on any assignment was failure of the course.

As noted above, the AIC imposed or recommended additional sanctions in 4 cases (3 Letters of Censure; 1 recommendation for dismissal). One AIC investigation is still pending.

Discussion

The Academic Integrity Committee sees 4 major issues for discussion.

- the challenge of ensuring equity in our academic integrity system

- the challenge of contract cheating

- the need for support for faculty

- the need for a revision of sanction structure

The Challenge of Equity

USF has done an effective job in designing an academic integrity process that treats students equally: all students involved in academic integrity cases are given the same information and opportunities; they all have the same rights and responsibilities. However, there are signs of series gaps in equity. Equality often means treating each individual the same way, whereas equity means helping different people and groups achieve similar outcomes or goals. Although the academic integrity system treats students equally, we see very large differences in outcomes for different demographic groups.

In other words, we have a fair process, but without an equity-minded approach, we as an institution effectively produce unfair outcomes for our students.

Bensimon et al. (2007) define equity-mindedness as including three ways of approaching data about student performance or achievement:

- We must “develop awareness of race-based inequalities in educational outcomes.”

- We must “interpret race-based disparities in educational outcomes through the lens of equity.”

- We must “view inequalities in outcomes as a problem of institutional accountability that calls for collective action.”

The Academic Integrity Committee argues we should apply Bensimon’s concept of equity-mindedness to the academic integrity outcomes of many demographic groups, including international students, students belonging to groups traditionally underrepresented in higher ed, Pell Grant-eligible students, and transfer students. An awareness of differential impacts of the academic integrity system helps us to focus on equity of outcomes in addition to equality of process.

International students

International students are strongly over-represented in academic integrity cases. In Fall 2019, 1478 international students were enrolled at USF, out of a total student population of 10,636, or just under 14% of the student population. Yet 48 of 66 reported incidents, or 73%, involved international students. Since international students are more frequently reported, they are also thus more frequently sanctioned by faculty and by the Academic Integrity Committee.

Either international students are violating the Honor Code at a higher rate, or they are caught and reported at a higher rate, or a combination of both. There are likely multiple causes for this disparity, including:

- We know that every culture values honesty and integrity, but “the details differ and the values and expectations placed on these practices differ” in different cultural contexts (Blum 2007).2

- Some risk factors for cheating may be more acute for international students, including isolation, stress, or unfamiliarity with institutional norms (Bertram Gallant et al. 2015).

- Some violations, particularly some forms of plagiarism, may be based in students’ prior learning in their home country. As Donahue (2008) observes, “French education does not emphasize avoiding plagiarism as we know it; in fact, some French writing and teaching practices can even encourage it.”

- Language differences and unfamiliarity with context may cause international students to be caught and reported at higher rates; in other words, they may cheat less deftly than domestic students

- There may be unconscious or other bias affecting faculty reporting.

An equity-minded response to these data would be to understand the disparity as an indicator of institutional underperformance and not as a consequence of student deficits (Wood & Harris 2020). We see in this data an urgent call to better support international students in navigating academic integrity at USF.

2 Mann et al. (2016) similarly find that “culture influences dishonesty primarily by establishing norms for the acceptability of dishonest behavior in specific situations” (p. 870).

Under-represented groups

Among domestic students, it appears that students from underrepresented groups are at greater risk than students in majority groups for being reported for Honor Code violations: two-thirds of domestic students reported for Honor Code violations appear to belong to groups traditionally underrepresented in higher education. More research is needed here: this is a very small sample of a relatively short time period (12 domestic students total were reported in 2019-2020).

Transfer Students

Bertram Gallant et al. (2015) find transfer students at a higher risk for being reported for cheating. Since the transfer student population substantially overlaps with other vulnerable populations, this is an area for concern. Transfer students comprised 17.5% of undergraduate students reported for Honor Code violations in 2019-2020.

We are sobered by the prospect that our most vulnerable students may also be those most heavily penalized by our academic integrity systems, and we see in these data an urgent call for more study, as well as for more support for students and faculty as they navigate academic integrity at USF.

Variation in faculty-imposed sanctions

Although we approve of the discretion USF gives to faculty members, we see disparities, sometimes very large, in penalties given to students. In one course, a student might be given an opportunity to re-write an assignment or do extra work; in another, a student committing a similar offense might fail the course entirely.

Analysis of these disparities shows that individual faculty members tend to apply sanctions very consistently in their own courses. We do not see great variations in penalties given by individual faculty members. An example of a potentially troublesome variation would be that one student gets a warning, while another student with the same violation in the same course gets an F—we do not see this kind of potentially unfair variation in reports received in 2019-2020. Instead, the variation emerges between different faculty members: in one course, there may be rehabilitative options; in another, students may face severe consequences without recourse.

We do not see any faculty-imposed sanctions that are markedly out of line with the USF Honor Code and the norms of US higher education generally. However, current scholarship on academic integrity argues against penalties such as failure of a course. Howard (1995) describes this kind of consequence as an “academic death penalty.”

While preserving faculty independence and judgment, we need to do more to support faculty members in creating learning environments that support integrity (so fewer students will cheat) and we need to help faculty respond fairly when violations occur (see Lang 2013).

Challenge of Contract Cheating

“Contract cheating” is when a student hires a “contractor” to complete coursework (for example, a ghostwriter to write an essay or a programmer to generate code). This form of cheating may be harder to detect than the more familiar forms of “cut-and-paste” copying and also may be harder to detect in online coursework.

A new feature of contract cheating is the organized ensnaring of students through predatory social-media advertising. We also know that USF students can obtain ghostwriting services locally, including from other USF students (Zheng & Cheng 2014).

Currently, this form of academic fraud is difficult to detect using technology, although plagiarism-detection services such as Turnitin.com are attempting to address it. The most reliable tool we have for preventing contract cheating is a faculty member who nurtures strong student-teacher relationships (Bretag et al. 2019). The most reliable existing tool for detecting contract cheating is a faculty member who reads student work carefully throughout a semester, and notices features that are alarm bells for contract cheating, such as:

- unexplained variation in voice or style

- unexplained variation in citation practices

- unexplained content variation (for example, a drastic change of topic between proposal and final draft)

- mismatches between a student’s in-class writing and formal assignments

- mismatches with course content or assignment parameters

As Bretag, et al. (2019) argue, “To minimise contract cheating, our evidence suggests that universities need to support the development of teaching and learning environments which nurture strong student-teacher relationships, reduce opportunities to cheat through curriculum and assessment design, and address the well-recognised language and learning needs of LOTE [language other than English] students.”

Needed Faculty Support

Supporting fairness in faculty responses to violations

USF faces a challenge of balancing faculty discretion and independence with an obligation for fairness for students across different schools and courses. Beyond the text of the Honor Code itself, no structure exists at USF to support faculty in their decision-making or to harmonize systems in different schools, departments, and programs.

It’s hard to defend the fairness of drastically different penalties for similar violations. Outreach and professional development opportunities may help bring faculty members across the university into greater alignment.

Supporting research-based pedagogical strategies

Many practices in higher education rely more on tradition than on research-based knowledge about human behavior. This is also true of our penalty-based system for supporting academic integrity in the USF community.

As Howard (1995), Davis et al. (2009), Lang (2013) and many others have argued, many and even most student breaches of academic integrity are “a pedagogical opportunity, not a juridical problem” (Howard, p. 788). This is particularly true of many forms of plagiarism, such as those involving citation errors or “patchwriting” (defined by Howard as “copying from a source text and then deleting some words, altering grammatical structures, or plugging in one-for-one synonym-substitutes.” Lang (2013) argues that designing courses to “reduce both the incentive and the opportunity to cheat” actually provides better learning experiences for all students.

Nothing in USF’s Honor Code forbids faculty members to use transgressions as learning opportunities, or departments to establish guidelines or policies along these lines. However, the current Honor Code is silent on this question and does not recommend any specific courses of action.

Encouraging reporting

Patterns of Honor Code incident reporting present us with several mysteries. Understanding and addressing the concerns raised by these patterns should be a high priority of the USF community.

The Academic Integrity Committee believes that many instances of academic dishonesty go undetected, and even when dishonesty is detected, it is not always reported to the AIC. Reporting patterns support this view.

For example, students in the School of Management account for almost half of the incident reports submitted, but only 8% of incident reports come from SOM faculty. This disparity may be partly explained by the fact that students are more likely to cheat in non-major courses, in courses where they experience low intrinsic motivation, or where they see low relevance to their educational goals. Thus SOM students may be more likely to cheat in Arts & Sciences courses. Another possible explanation for the disparity in reporting is that compared to CAS faculty, SOM faculty are either less likely to catch violations or less likely to report violations, or a combination of both.

Faculty members may choose not to report an offense for a number of reasons, including:

They may want to resolve locally so they have more control over the situation, including shielding students from potentially punitive measures at the University level.

They may feel uncertainty about potential consequences for them as employees: Is it rocking the boat to report students to the AIC? Is it considered a pedagogical failure to have students cheat in my course?

The USF process may be unfamiliar or opaque, particularly for new faculty or adjuncts working at multiple institutions, who deal with different procedures and stakes at each school.

The process may be perceived as burdensome for busy faculty; or it may involve unforeseen time commitments (such as being tangled up in an investigation).

Since accused students still have the right to fill out end-of-semester ratings of faculty performance, vulnerable faculty members may see reporting as an employment risk

50% of the cases in 2019-2020 were reported by adjunct professors, a positive sign in that adjuncts are most vulnerable to the pressures/obstacles listed above. However, this is still an underrepresentation, as part-time faculty make up about 60% of the USF faculty.

More research is needed into obstacles to reporting and patterns of reporting. Additionally, continued outreach efforts and greater transparency (such as dissemination of this report) may help reduce obstacles to faculty participation.

Future Goals

The AIC can do better in the future in reaching out to the campus community; this report is imagined as a step in this direction.

We also hope to continue partnerships with Student Services, Deans’ offices, and with the Seeley Center for Teaching Excellence.

In 2018-19, the Academic Integrity Committee prepared a proposal for a substantial revision of USF’s Honor Code. Adoption of this proposal depends, in our view, on close collaboration of the Provost’s Office and the USFFA-FT and USFFA-PT. Contentious contract negotiations, upheaval in the Provost’s Office, and a global pandemic have interfered with bringing this proposal forward. We plan to introduce the proposed revision to the Honor Code to the Provost’s Office and the USFFA Policy Boards in August 2020.

Key aspects of the proposal include:

The current Honor Code, which runs to almost 3500 words, is split into three documents:

- Students, faculty, and staff will have access to plain-language explanations of all aspects of the Honor Code and Academic Integrity Committee procedures (we have seen that many students have difficulty parsing the legalese of the current Honor Code).

- the Honor Code itself, a short document emphasizing the mission and positive values of USF, as well as the conduct associated with those values (public facing).

- the procedures of the Academic Integrity Committee, including student rights and responsibilities, incident reporting, timelines, possible sanctions, etc. (campus facing).

- the by-laws of the AIC, including composition of the committee, responsibilities of members, term length, etc. (committee facing).

- In addition to existing punitive sanctions (Letter of Censure, Suspension, Dismissal), the Honor Code will include an educational sanction, a 2-unit Academic Integrity course that the AIC may recommend as an option for students in exchange for a reduction in penalty.

- The current Honor Code holds that “members of the faculty, staff, or the student body who witness or suspect they have witnessed a violation of the honor code [...] are bound by the honor code to report the violation”; this provision is removed.

- An important change in the timeline is recommended: currently, students must decide whether or not to call a hearing to contest the findings of the AIC before learning of the sanction that awaits them. We propose that the student should have the right to call for a hearing after learning of the AIC’s recommendation for a sanction.

Bibliography

Ambrose, S. et al. (2010). How learning works. Jossey-Bass.

Ariely, D. (2012). The Honest truth about dishonesty: How we lie to everyone—especially ourselves. HarperCollins.

Bertram Gallant, T. (Ed.) (2010). Creating the ethical academy : A systems approach to understanding misconduct and empowering change. Taylor & Francis.

Bertram Gallant, T., Binkin, N. & Donohue, M. (2015). Students at risk for being reported for cheating. Journal of Academic Ethics 13, 217-228.

Blum, S. D. (2007). Lies that bind: Chinese truth, other truths. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Blum, S. D. (2009). My Word! Plagiarism and college culture. Cornell University Press.

Bretag, T. et al. (2019) Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), 1837-1856.

Davis, S. F., Drinan, P. F., & Bertram Gallant, T. (2009). Cheating in school : what we know and what we can do. Wiley-Blackwell

Donahue, C. (2008). When copying is not copying: Plagiarism and French composition scholarship. In M. Vicinus, & C. Eisner (Eds.), Originality, imitation, and plagiarism: Teaching writing in the digital age (pp. 90-103). University of Michigan Press.

Howard, R. M. (1995). Plagiarisms, authorships, and the academic death penalty. College English 57(7), 788-806.

Lang, J. (2013). Cheating lessons: Learning from academic dishonesty. Harvard University Press

Mann, H., Garcia-Rada1, X., Hornuf, L., Tafurt, J., & Ariely, D. (2016). Cut From the same cloth: Similarly dishonest individuals across countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 47(6), 858-874.

Wood J. L. & Harris, F. (2020). Employing equity-minded & culturally-affirming teaching and learning practices in virtual learning communities. Center for Organizational Responsibility and Advancement.

Zheng, S. & Cheng, J. (2015) Academic ghostwriting and international students. Young Scholars in Writing 12, 124-133.

Appendix 1: Committee Membership 2019-2020

Jonathan Hunt (co-chair, 2018-2019; chair, 2020)

Doreen Ewert (co-chair 2017-2019)

Megan Bolitho

Fernando Comiran

Ryan Garcia

Karen Gibson

Amy Gilgan

Denora Guevara

Annie Han

Jessica Kench

Andrew Lee

Genevieve Leung

Dan McPherson

Dhara Meghani

Melly Merida

Tom Merrell

Byanka Mexia Monzon

Nicole Nguyen

Leyla Perez-Gualdron

Liam Quinn

Mehrnoush Shahhosseini

Michael Torre

Hannah Weeks

Appendix 2: Policies and Procedures Overview

For a full account of the procedures of the Academic Integrity Committee, see the USF Honor Code (https://myusf.usfca.edu/academic-integrity/honor-code).

We include an overview here to aid in the reading of this report.

Student Rights

Students who are accused of an honor code violation have the right to defend themselves against any and all charges levied against them. Students may gather and submit evidence and recruit witnesses in their defense. Students also have the right to bring a case to the Academic Integrity Committee themselves if they believe they have been falsely accused. Students may also appeal the initial decision of the Academic Integrity Committee through a request for a formal hearing.

The AIC has no jurisdiction over grade disputes. If a student wishes to appeal a grade, they must follow the procedures established by their college or school.

Incident Reports

All members of the USF community are encouraged to alert the AIC if they witness or suspect a violation of the Honor Code.

Faculty members do not need to “prove” a violation in order to send the AIC an incident report. There is no burden of investigation or proof required to file an incident report.

In the large majority of incidents, individual faculty members communicate with students about violations of the Honor Code and determine consequences according to course policies, department or program policies, and the Honor Code itself. The incident report to the AIC is for record-keeping only.

On behalf of the AIC, the Office of Student Conduct, Rights, and Responsibilities keeps records of all reports. However, the AIC does not investigate or determine additional university-level sanctions, except under specific circumstances (if there is a repeat violation; if the violation is judged to be grave or severe; if the student requests an investigation).

Investigation

In approximately 90% of cases, the role of the AIC is simply record-keeping. As per the Honor Code, the AIC investigates cases and levies sanctions only under specific circumstances:

- if the report indicates a second offense or a grave offense

- if the student contests and accusation and requests an investigation

An “investigation” consists of interviews by a team of 2 or 3 Committee members. This team interviews the people involved in an incident and reviews available evidence. The team reports back to the full AIC with a recommendation on two questions:

- Did a violation of the Honor Code occur?

- If a violation did occur, what sanction, if any, is recommended?

Sanction

Following an investigation, the AIC votes on the two questions (above).

If the first vote finds no violation, the incident report is removed from the student’s record and the AIC notifies the student, the reporting individual, and the Associate Dean of the student's school or college. The student may choose to pursue a grade appeal according to applicable procedures.

If the first vote finds a violation, the student is notified and has the opportunity to respond. If the student contests the finding, a hearing is called (see below). If the student accepts the AIC finding of violation, the AIC then moves to the second vote, regarding sanction. In some cases, the AIC considers sanctions imposed by the faculty member to be sufficient and does not add any university-level sanction. In others, the AIC may vote to add a university-level sanction. The three options are: Letter of Censure, Suspension, or Dismissal from the University. In the case of a vote for suspension or dismissal, the AIC vote is presented to the Provost as a recommendation.

- Letter of Censure. This letter describes the honor code violation and is placed in the student’s academic file. The letter is kept on file for seven (7) years, at which time it is destroyed.

- Suspension. Suspension is usually one semester, but may be imposed for two semesters. Suspension is noted on the student's transcript at the end of the semester’s entries in which the violation occurred.

- Dismissal/Revocation of Degree. Dismissal is noted on the student’s transcript at the end of the semester’s entries in which the violation occurred. If a student has already received a degree from the University, the President or Provost of the University may revoke the degree. The sanction will be entered permanently on the student’s record.

Once a sanction is recommended by the AIC, there is no mechanism for appeal.

Hearing

If a student disputes the Academic Integrity Committee’s finding of a violation, they have the right to request a hearing. In the current system, the student must call for a hearing after the finding of a violation, but before knowing the sanction.

A hearing convenes at least five members of the AIC to consider the student’s case; the student may present arguments and evidence and invite witnesses to testify. The student is also entitled to be accompanied by a support person or observer; however, legal counsel is not permitted at the hearing.