Backward Course Design

Written by Jori Marshall & Austin Palaad

August 15, 2019 • 3 minute read

Like architects or software developers, educators are designers. For instance, instructors seek to make a tool (coursework) more effective for their clients (students). The traditional approach of relaying coursework to students usually involve prioritizing breadth over depth; with an emphasis on content-focused curricula vs. results-focused curricula. Wiggins and McTighe, authors of Understanding by Design (2005), offer “twin sins” of traditional course design. The first sin being activity-oriented design; that “lead, only, accidentally to insight or achievement”. The second sin is “coverage”; an effort to successfully survey the literature by “attempting to traverse all the factual material within a prescribed time”.

While both of these design structures are not inherently wrong, according to Wiggins and McTighe (2005), they offer no guiding intellectual purpose or clear priorities to frame the learning experience. This creates ambiguity around meaning with hopes that it will somehow become apparent for the student with no clear expectation of goals. The solution to this problem would involve “Backwards Course Design”, where units, lessons, and courses are logically modeled from specific results desired.

Backward Course Design is an approach that prioritizes “Learning-Centered Teaching”. According to Dr. Nitza Davidovich of Ariel University, learning-centered teaching emphasizes the nature of the learner’s process. This approach is based on the concept that the complete transference of knowledge in its form cannot happen rather learners must have the ability to uncover or obtain knowledge independently. Backwards course design originates from STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) educational disciplines and has primarily been applied to K-12 learning.

However, according to researchers in education, the approach of backwards course design has been increasingly utilized by scholars of higher education. A research study implemented by scholarly writers on intentional teaching and scholarship present evidence that principles of backward design are profitable to scholarly production and motivation and similarly to course design in higher education. By making expectations and goals clear, instructors who utilize backwards course design can revitalize their classrooms, notice an increase in motivation from their students, boost confidence in student learning, and see an increase in student participation.

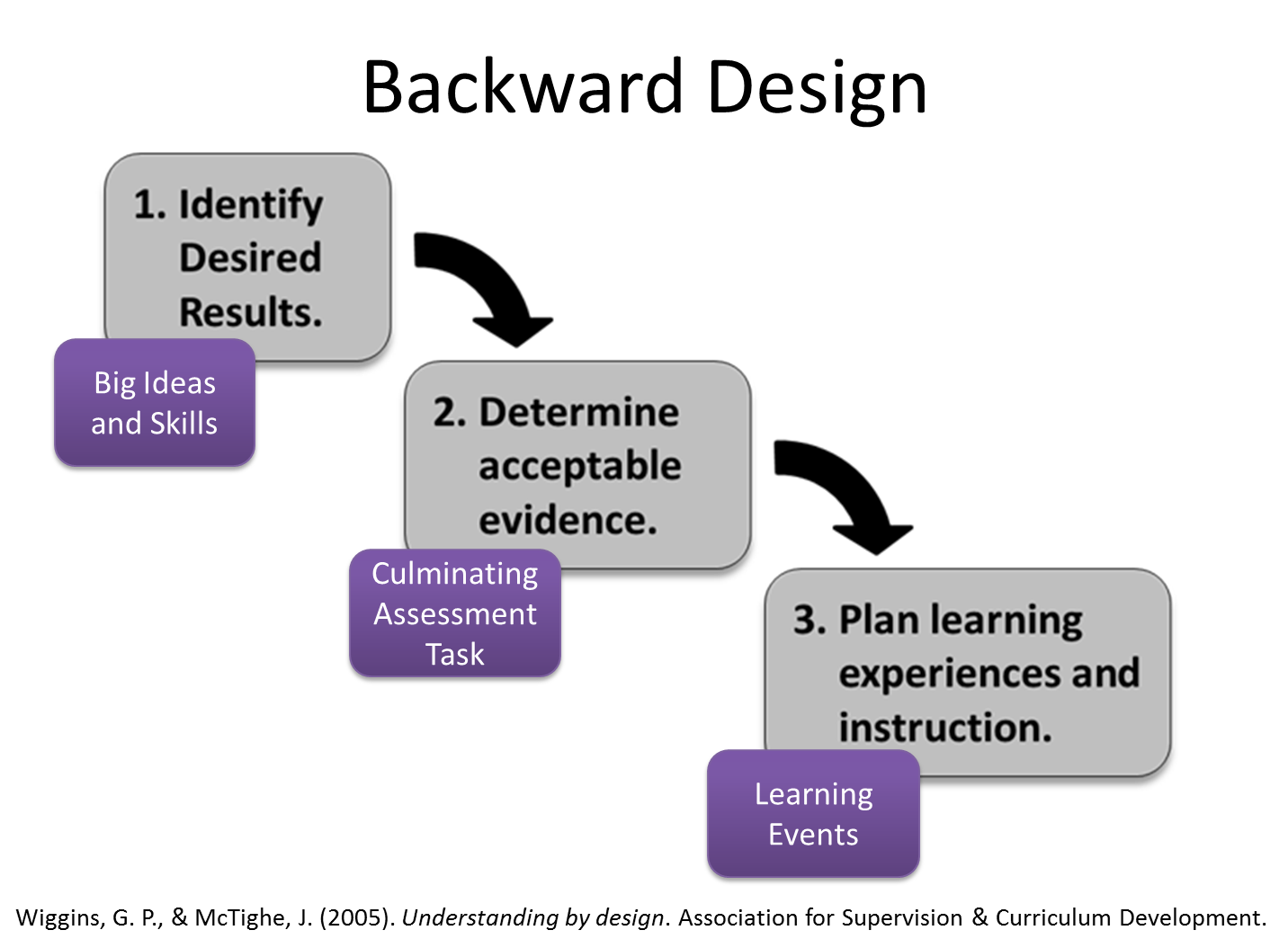

As the first discipline to adopt this unique approach, STEM disciplines planned in four stages in order to map the outcome of desired results. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) offer three stages of planning a course for educators. Those three stages of backwards design include:

Stage 1: Identifying desired results: What should students know, understand, and be able to do?

Stage 2: Determine acceptable evidence: How will you know if students have achieved the desired results?

Stage 3: Plan learning experiences and instruction: What enabling knowledge and skills will students need in order to perform effectively and achieve desired results?

Identifying desired results

Content worthy of understanding is an ideal place to start to begin your course planning with backwards design. What are continuous understandings you expect your students to acquire? Consider your objectives and review district, state, and/or national content standards. Because there is usually a great deal of subject matter to address in a given amount of time, the clarification and prioritization of content and preeminent material is important in this step.

Your objectives and goals for the course should not be tied to the course activities themselves, but instead to the significance of these activities. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) provide three questions that you can ask yourself to establish curricular priorities:

- What should participants hear, read, view, explore or otherwise encounter?

- What knowledge and skills should participants master?

- What are big ideas and important understandings participants should retain?

Stage 1 design:

According to the Understanding by Design (UbD) template, designers are prompted to frame understandings expected of students in terms of questions that are guided by established goals. For example, “Students will understand that: What specific understandings about them are desired? What misunderstandings are predictable?”.

Determine acceptable evidence

This stage focuses on defining the ability to know that students have achieved the goals expected of them in their courses. What evidence will you accept of student understanding and proficiency? Instructors are encouraged to “think like an accessor” prior to the design of fixed lessons and units. In stage two, you will explore multiple ways of assessing for the gathering of evidence of desired comprehension. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to what assessments best suits your course, but try to keep in mind that your style of assessment should be the most transparent and obvious evidence of student proficiency.

Stage 2 design:

The UbD template encourages you as an instructor to organize your assessments. Following the organization of assessment methods, create a space for identifying specific assessments you plan to utilize during your lesson or unit. Instructors are encouraged to think in terms of gathered evidence contrary to a single test or performance task.

Plan learning experiences and instruction

The final stage of backwards design is the stage that traditionally leads course planning for instructors. However, with clear outcomes and plans on relevant evidence of comprehension, you will be able to begin the process of fully considering the most applicable and appropriate instructional activities. This can be compared to using a map; provided a destination, what is the most practical and efficient route?

Guiding questions to begin this process are provided by Wiggins and McTighe (2005):

- What activities will equip students with the needed knowledge and skills?

- What will need to be taught and coached, and how should it best be taught in light of performance goals?

- What materials and resources are best suited to accomplish these goals?

Stage 3 design:

Within the UbD design template, stage three requires a listing of primary learning activities where you as the designer must be able to recognize what Wiggins and McTighe (2005) call the “WHERETO” elements:

- W- Helps the students know Where the unit is going, What is expected, and helps the teacher know Where the students are coming from.

- H- Hook all students & Hold their interests.

- E- Equip students, help them Experience the key ideas and Explore the issues.

- R- Provide opportunities to Rethink and Revise their understandings and work.

- T- Be Tailored (personalized) to the different needs, interests, and abilities of learners.

- O- Be Organized to maximize initial and sustained engagement as well as effective learning.

Wiggins and McTighe (2005) note that although the three stages are presented in order, backwards course design does not necessarily follow a “step-by-step” process. Where you start in the stages of backwards design is not essential if your outcome is a clear and articulate design that follows the logic of the three stages. If you are an instructor and up for the challenge of becoming more intentional in course design in hopes of improving and increasing student engagement and understanding, backwards course design is the most effective approach to aid in your pedagogy practices.

Are you or someone you know finding success with backwards course design? If so, we’d love to hear from you! Email instructionaldesign@usfca.edu to share your story.

Whether you don’t know where to start or have a particular educational technology in mind, we are here to help! To learn how to apply educational technologies to your course, request an Instructional Design consultation.

Contact Instructional Technology & Training to schedule a training session and access self-guided training materials on educational technologies supported at the University of San Francisco.

Resources

- Backward Course Design: Making the End the Beginning (Daugherty, 2006, American Journal of Pharmacy Education)

- A Planning Tool for Incorporating Backward Design (Reynolds & Kearns, 2016, College Teaching)

- Understanding by Design: Mentored Implementation of Backward Design Methodology at the University Level (Michael & Libarkin, 2016, Journal of College Biology Teaching)

- AACU: VALUE Rubrics - Foundations and Skills for Lifelong Learning

- Indiana University: Backwards Course Design Worksheets and Checklist

Research

- Understanding by design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, book)

- Intentional Teaching, Intentional Scholarship: Applying Backward Design Principles in a Faculty Writing Group (Linder et al., 2014, Innovative Higher Education)

- Learning-Centered Teaching And Backward Course Design From Transferring Knowledge To Teaching Skills (Davidovitch, 2013, Journal of International Education Research)